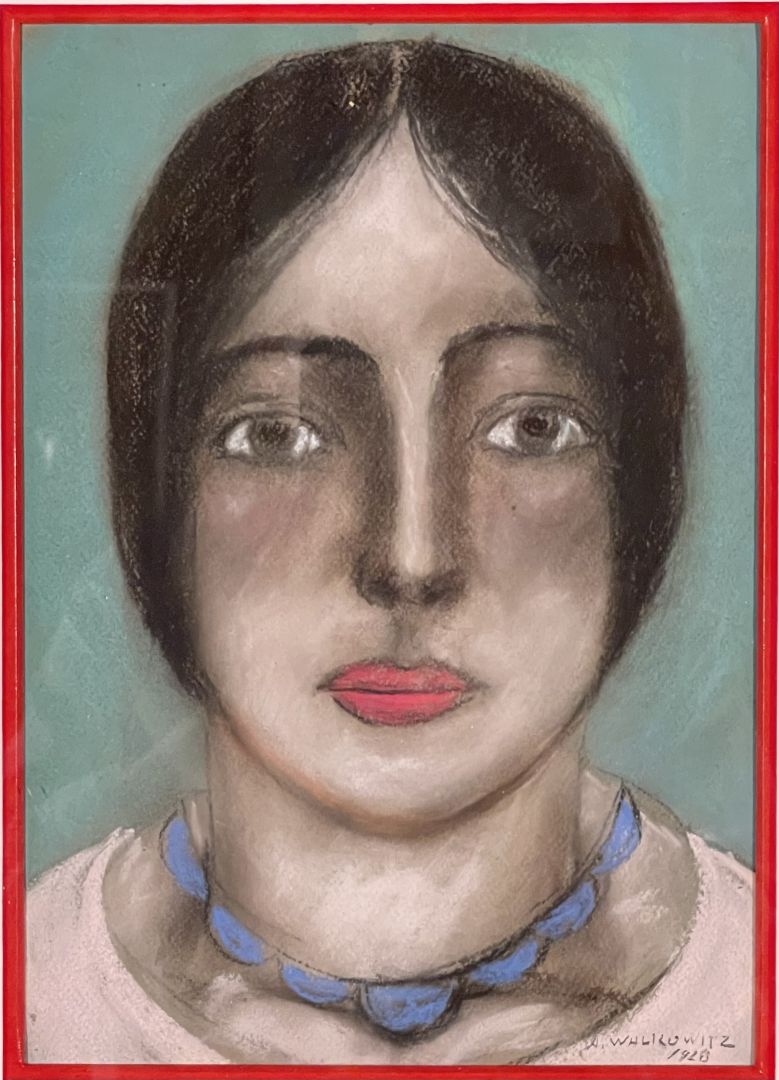

Walkowitz, Abraham (American, born Ukraine, 1878-1965). PORTRAIT OF ISADORA DUNCAN. Pastel on paper, 1928. Signed lower right. 12 x 8 1/4 inches, framed to 17 x 13 inches. The verso of the frame also has a label signed by Walkowitz. Walkowitz grew up in New York; in 1906, he went to Paris to study painting at the Academy Julien. The painter Max Weber introduced him to Isadora Duncan in Rodin's studio. His interest in Duncan as a subject began then and lasted beyond her death in 1927; he made more than 5000 drawings and paintings including more than a few pastel portraits like this one, and a great many pieces of her performing. As with this piece, done after her death, it is likely that many of the works were done from memory rather than from life. "He was also able to draw from the same subject repeatedly and extract a different experience with each observation" (Wikipedia article). In this, his use of Duncan as a subject seems similar to Giorgio Morandi's repeated use of a handful of cups, bottles and bowls to create a large number of still-life paintings, drawings, and prints each of which has something new to offer.Walkowitz was at the center of American Modernism, part of Stieglitz's circle at 291 from 1911 to 1917, and a participant in the Armory Show.The following from the Wikipedia article on Walkowitz is a discussion of his Duncan drawings:In 1927, Isadora Duncan echoed the lines of Walt Whitman in her essay I See America Dancing, writing, "When I read this poem of Whitman’s I Hear America Singing I, too, had a Vision: the Vision of America dancing a dance that would be the worthy expression of the song Walt heard when he heard America singing."[4] Duncan was the quintessence of modernism, shedding the rigid shackles of the balletic form and exploring movement through a combination of classical sculpture and her own inner sources. She described this search: "I spent long days and nights in the studio seeking that dance which might be the divine expression of the human spirit through the body’s movement."[5] For Duncan, dance was a distinctly personal expression of beauty through movement, and she maintained that the ability to produce such movement was inherently contained within the body.Abraham Walkowitz was one of many artists captivated by this new form of movement. The Duncan drawings can be interpreted as representations of Walkowitz's loftiest goals. Composing thousands of these drawings would prove to be one of the most effective outlets for his artistic agenda due to the similarities between the artistic ideals and preferred aesthetic shared by Walkowitz and Duncan. He was also able to draw from the same subject repeatedly and extract a different experience with each observation. Sculptors most readily recognized this trait in Duncan; there was a particular quality of her dance which appeared readily artistic, yet not static. Dance critic Walter Terry described it in 1963 as, "Although her dance inarguably sprang from her inner sources and resources of motor power and emotional drive, the overt aspects of her dance were clearly colored by Greek art and the sculptor’s concept of the body in arrested gesture promising further action. These influences may be seen clearly in photographs of her and in the art works she inspired."[6]Isadora Duncan #29, c. 1915In each drawing, a new observation is recorded from the same subject. In the Foreword to A Demonstration of Objective, Abstract, and Non-Objective Art, Walkowitz wrote in 1913, "I do not avoid objectivity nor seek subjectivity, but try to find an equivalent for whatever is the effect of my relation to a thing, or to a part of a thing, or to an afterthought of it. I am seeking to attune my art to what I feel to be the keynote of an experience."[7] The relaxed fluidity of his action drawings represent Duncan as subject, but ultimately reconceive the unbound movement of her dance and translates the ideas into line and shape, ending with a completely new composition.His interest in recording the "keynote" of experience rather than producing an objective representation of a subject is central to the composition of the Duncan drawings. The fluidity of the lines function simultaneously as recognizable shapes of the human body, but also trace the pathways of the dancer's movements. Duncan herself wrote in 1920, "...there are those who convert the body into a luminous fluidity, surrendering it to the inspiration of the soul."[4] Placed into a different context, this passage could function as a description of Walkowitz's art; it is in fact taken from her essay The Philosopher’s Stone of Dancing wherein she discusses techniques to most effectively express the purest form of movement.Walkowitz's dedication to Duncan as a subject extended well past her untimely death in 1927. The works reveal shared convictions toward modernism and breaking links with the past. In 1958, Walkowitz told Lerner, "She (Duncan) had no laws. She did not dance according to the rules. She created. Her body was music. It was a body electric, like Walt Whitman. His body electrics. One of our greatest men, America's greatest, is Walt Whitman. Leaves of Grass is to me the Bible."[8]

Follow us

Contact Us

ed@edpollackfinearts.com

Copyright © 2026 - Edward T. Pollack Fine Arts